The Roots of my Indigenous Identity

A story of my wildly complicated entry into the politics of Indigenous identity

Though significantly revised, this is based on content that originally appeared in a term paper for a class in my Masters program, December 2008:

Growing up, I had only the dimmest awareness of the politics of Indigenous identity.

I was Métis, which I understood to mean that I had a white parent, and an Indian parent (though I know now that the true definition of Métis identity is more complex). I never questioned this identity either.

You would have never known it to look at me…pale, blonde, English-speaking; but I was Indigenous, and I was told to be proud of it. There were also other kids like me around, who looked white (though maybe not as fair as I was) but were also Métis, Cree or Dene, so I saw nothing but a common thread running through Fort Smith. In other words, there as nothing for me to doubt.

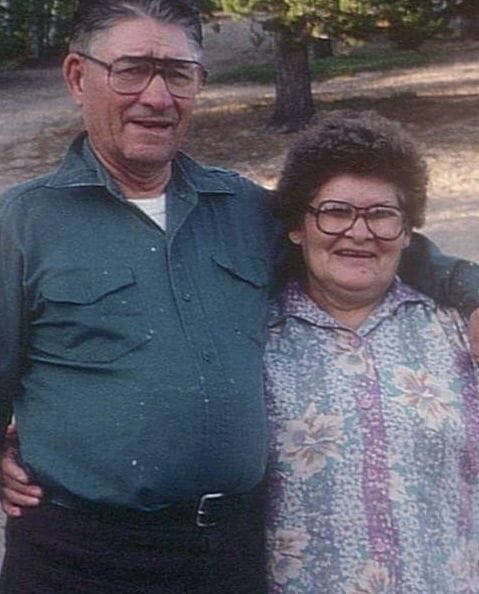

Why didn’t I question it, despite me looking so drastically different from all of my cousins? Because I spent a lot of time with my paternal grandparents, and as a wee child, my Grampa was insisting on using nehiyô familial names. They called us grandkids cicim. I was expected to call him mosôm and her nohkôm. My grandparents were clearly “Indians”1, with the trademark dark hair, brown eyes, and warm brown skin tones. They drank tea by the gallons, eat dried meats, and my Gramma’s bannock was the best treat ever. We went out berry picking, we had a cabin at Salt River, and my grandparents spoke Cree and Chipewyan. We listened to Northern radio where the news and weather could be delivered in a multitude of First Nations and Inuk languages, and my Grampa, a self-taught polyglot, understood a lot of what was said on air. The daily course of their lives just naturally announced “Yes, we’re Indigenous”.

Joseph Poitras and Christine Poitras (née Powder), Camp Caribou, 1980s.

Being too young to understand the complex history involving First Nations people in Canada, it never occurred to me that they (and by extension, my dad and I) were not legally defined as Indians.

In 1955, my grandfather was “enfranchised” under the Indian Act, meaning that he and his wife and children were removed from the Indian Registry; not willing to live according to the restrictions of the Indian Act, and wanting to build a home for his expanding family, Grampa voluntarily surrendered his legal identity for scrip and the Federal Government saw fit to strip him and his wife and kids of their Indian status and the entitlements to live on the Allison Bay Reserve at Fort Chipewyan, AB. This irrevocably changed the destiny of my family.

No longer connected, my Grampa took my Gramma and the younger kids out of Fort Chipewyan, to a logging camp along the Peace River. My grandparents did not continue to speak to the kids in their languages, instead favouring English, which would get them by in the wider world. They would eventually find their way North to Fort Smith and settle there.

As a child, I was not privy to this information; had I been, I would have been confounded by it. How was it possible that my Grampa wasn’t Indian? He looked, talked, and acted like one.

But by 1985, the adults were talking about something that threw everything I knew about myself and my family into a tailspin. Parliament enacted Bill C-31, An Act to Amend the Indian Act, allowing Indians who had lost their Indian status to regain it.

Despite being fully eligible, my Grampa was a proud man, and he was absolutely not going to bother, and because my Gramma stood by her husband, she didn’t either. Grampa died suddenly in 1988, and even then, Gramma didn’t want to. As a Métis woman, she left things at that.

On one non-descript day in 1991, I “became” a status Indian, without knowing it. I was well into high school before I became aware. I was home for lunch one day, and my dad came strolling in. I was a little surprised because he didn’t normally come home at lunch. After saying hello, my dad put a piece of paper on the kitchen bar top and told me to go to this address to get my status card. Being utterly clueless to what that meant, I wanted to ask, but my dad was not a prolific information-sharer, so I didn’t question anything. I didn’t understand; what was I, a shy, immature teenager, going to do? Just walk in and pretend like I knew what this meant?

I put it off for weeks, until my dad, fed up with my dithering, got mad, so off I went (alone). I was really scared when I walked into the office alone. A receptionist asked me if she could help me, and I nervously pulled out the paper and said my dad told me to come here to get some ID. She was clearly used to seeing these situations (though likely not a lone teenage girl), and before I knew it, I was led to a photo backdrop, where my photo was taken, and within minutes, I walked out with a laminated status card. I was still bewildered.

Over the years, I struggled to come to terms with what this means for my identity. And why wouldn’t I, in light of the fact that federal government, the Courts, Bands, and even the United Nations have all had a crack at defining my legal identity? After all, what was I before that day, and who decided how I was defined? Making sense of this change was my journey.

The paper I wrote for my class was my crack at unraveling the legal and legislative journey that led to the restoration of treaty status to my family and over 100,000 others across Canada, and understanding the consequences of this policy change. It took me down several rabbit holes of research, each bringing me further along in untangling the complex nature of my family’s history, laid against the backdrop of a colonial government taking a series of colonial decisions about us, without us.

Since I wrote that paper, several more pieces of federal legislation, spurred by Supreme Court cases, have widened the eligibility further, and the main thread in these situations is the continued gender discrimination baked into s.6 of the Indian Act. The Act is still going to change. As it stands now, under the Act, I am designated as a 6(2)—second generation cut-off, meaning that if I had had kids, they would not be entitled to be registered as First Nations, unless their father was a Status Indian falling under one of the subsections of s.6(1). But there are still several cases working their way through the Courts set on ultimately revising the Act to address all of the discrimination that continues.

You would think that by now, the federal government would understand that they are on the losing end of judicial precedence and ultimately stop thinking it gets to decided who is First Nations and who isn’t, but you’d be wrong. So, if you are working for CIRNAC or ISC, sorry, not sorry, but you need to get a message to your bosses that they suck at this. They need to stop being colonial gatekeepers, and to get out of the business, so to speak.

My journey continues, as I spend a lot more time unravelling the complexity of Métis identity and the far-less-well-known understanding of Inuit identity, and the social, legal and judicial landscape which has shaped those groups.

What I do know is this: The First Nations and Inuk Peoples who lived here long before European explorers and settlers had pretty sophisticated rules and customs governing recognition of who was a member of their society—it’s not the job of a damaging colonial government to usurp this responsibility.

When I was growing up, the term Indian was commonly used. Though it remains the legal terminology used for legislative purposes, it is no longer a widely-accepted term in First Nations communities.